Open Air 2021 Clive Humphreys Q&A with C R Lark

Big old trees are the keystone structures of forests on which many species depend.

George Monbiot The Guardian 13 August 2021

Tryst 2021 acrylic on canvas 1000 x 800mm

Q: Your new luminous treescapes mark a shift from black and white to colour, what motivated this change in your painting?

A: Despite working for so long in black and white, ironically I’ve always considered myself a colourist. After ten years of making monochrome charcoals and watercolours, which I deemed necessary in order to grasp tonal values of forest light, I then felt ready to use that knowledge in colour.

Q: What are the new concerns in these colour works?

A: They required a complete rethink. Building colour in translucent layers is a more complex proposition than a sole focus on tone. I needed to address shifting colour values within shadow, reflected colour and cast colour.

Q: Do you work in the studio or on site?

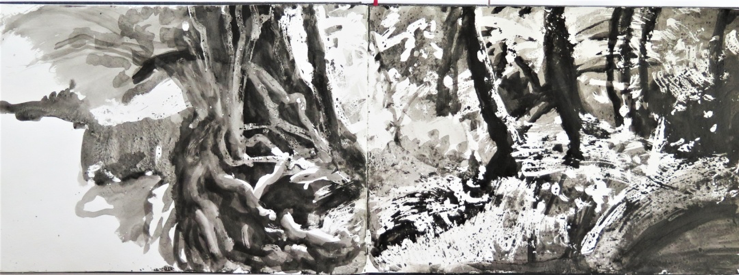

A: On site observational drawing has now become crucial as a foundation for studio painting, but sometimes it’s clear that a drawing is a finished work. I need to be within a place, to feel immersed rather than at a distance. I prefer to be outdoors with the sensory input of light, air, sounds and movement, surrounded by the subject to experience the specific characteristics of branches, leaves, light and shadow, soil, roots and the relationships between them. These studies in the open air often provide the groundwork for paintings that come later in the studio. Away from the saturation of place, the emphasis shifts to the demands and constraints of a composition. Making the painting work often requires a slower way of working, sometimes necessarily editing and modifying in order to unify the whole image.

Drawing book pages 2021

Q: What attracts you to a particular location?

A: I mainly work in a small area at Whakanewha Regional Park where the forest meets the shoreline, a sanctuary for nesting native birds on Waiheke Island. Whakanewha was an important Maori pa site with a large settlement supported by a plentiful food supply from land and sea. A track leads into a Nikau palm forest and I spent five years making interior forest drawings and paintings of the interwoven Nikau fronds between trunks and those fallen on the forest floor, which is both a cemetery and a nursery. This year my focus is on the ancient pohutukawa trees that stand in open spaces on the outermost edge of the bush near the ocean.

Q: Do these trees have a special significance for you?

A: Pohutukawa is a native species that can live up to one thousand years. These and other ancient trees are self-contained worlds protective of their own ecosystem with communication networks above and below ground. When I’m drawing, that sense of the tree’s connections extends to me as a participant, not only an observer. The quietness, the coolness of the shade and the movement of the air, the envelopment of the canopy, all combine to provide a natural shelter.

Shade 2021 acrylic on canvas 1000mm x 800mm

Q: What is the significance of the encounter with ‘a natural shelter’ for you?

A: The connotation is one of protection and by extension mutual dependence. As a child, I lived near to Epping Forest in Essex, England, where I liked to explore and I always felt in a benign presence surrounded by trees. I was alone in the forest, but not alone, a comforting solitude. Later as a teenager, I ran cross country races through Epping Forest and did solitary training on the forest tracks which consolidated those sensations.

Q: Would you say you have a sense of identification with the place where you’re painting?

A: Yes, I identify with that environment. In fact, the act of drawing requires a fundamental bodily identification with the trees: a transposition of sight into gesture. Many painters like to tidy the landscape as if it were a suburban garden, which seems to me a resistance to the complexity of nature. I’ve always been drawn to organic untidiness. My painting is an acknowledgement of detritus and messy death. But the painting is not the place; it’s a physical response through a manipulation of materials that describes my relationship with the forest architecture.

Q: What do you mean by the term ‘forest architecture’?

A: The disposition of the ancient trees, the way they interlock with one another as well as each tree’s individual structure. Pohutukawa grow branches that can turn into roots to support the tree and probe fissures in the rocks for moisture. Some branches act as pillars and some as crossbeams. So the analogy with architecture extends from individual tree structures to the forest as an interdependent network. Forest architecture has an understated grandeur.

Quag 2021 acrylic on canvas 1000mm x 800mm

Q Has this encounter with forest architecture in any way changed your working methods?

A: Yes. My growing commitment to observational drawing contradicts much of my formal training that promoted the value of drawing, but was actually more concerned with distilled generalisations. My student understanding and experience of Modernism was of a process of simplification, a paring away of detail in search of a Platonic essence, gleaned more from what was unsaid than directly stated during crits, when lecturers would suggest erasure and abbreviations, the subtext was always to get rid of what was labelled as extraneous elements. The effect was that subjects became summarised.

Q: At art schools in the sixties Minimalism was fashionable, viewed as striving towards essential truths. Did you agree with your lecturers suggestions?

A: I was persuaded at the time. But truth, as a reductive impulse, no longer seems viable to me. However, my instinctive aesthetic, forged through my formative years at art school, is still Modernist. The consequence is a tension between complexity, as evident in the natural world, and learned Modernist habits. This conflict plays out on the painted surface and is a dilemma shared by many whose working life spans major shifts in attitudes to the practice of painting

Q: What are your materials for these new colour works?

A: Acrylic paint on canvas and paper. This was my preferred medium until 2010, so I’m familiar with the requirements, but the way I use acrylics has changed radically over a decade, informed by using watercolour and exploiting its transparency. Acrylic washes can be achieved via glazing mediums, simply adding water weakens the surface integrity of the painting.

Q: How do you achieve the textural qualities in the work?

A: In both watercolours and acrylic paintings, I use a liquid stop-out to create stencil-like brush marks, which I later erase to reveal the underneath colour. Working from light to dark protects the lighter layers beneath. This technique borrows heavily from my printmaking experience.

Q: How important is technique for you?

A: Technical considerations are central to the painter’s task. Paint has a neutrality as a material; it doesn’t even need to be applied with a brush or in any prescriptive way. However, the method of application is integral to what the image describes.

Q: Given the climate crisis, do you consider these tree portraits as political alerts?

A: That’s not my intention. Nonetheless, I’m making these paintings in the context of current dire environmental circumstances. A particular focus on a small local area of thriving trees seems more relevant than a generality about deforestation. The choice to prioritise external observation over didactic issue-driven work is inherently a political decision.

Wash 2021 acrylic on paper 830 x 450mm

The deepest thing we can learn about nature is not how it works, but that it is the poetry of survival. The greatest reality is that the watcher has survived and the watched survives. It is the timeless woven through time, the cross-weft of all being that passes. Nobody who has comprehended this can feel alone in nature, can ever feel the absolute hostility of time.

John Fowles “The Blinded Eye” Animals, Vol. 13, No 9, January 1971